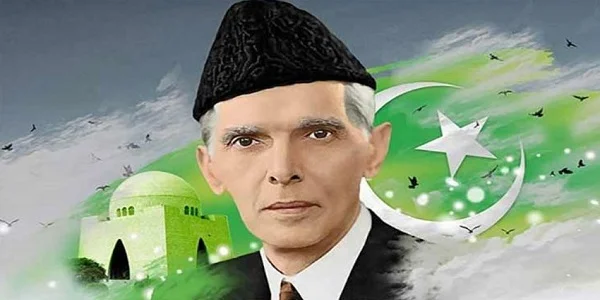

Muhammad Ali Jinnah

Muhammad Ali Jinnah, widely revered as Quaid-e-Azam (meaning "Great Leader"), was a towering political figure and statesman who played a pivotal role in the creation of Pakistan. Born on December 25, 1876, in Karachi, then part of British India, Jinnah emerged as the driving force behind the establishment of a separate nation for Muslims, leading to the formation of Pakistan in 1947. His life, marked by dedication to the principles of justice, equality, and self-determination, continues to inspire generations and remains integral to the history of South Asia.

Early Life and Education:

Jinnah hailed from a prosperous Gujarati Muslim family. His father, Jinnahbhai Poonja, was a successful merchant and his mother, Mithibai, was a woman of strong character. Jinnah received his early education in Karachi and later moved to London for higher studies. In 1893, he joined the Lincoln's Inn to study law, and in 1896, he was called to the bar.

Jinnah's exposure to Western political thought and legal principles during his time in London significantly influenced his worldview. He imbibed notions of justice, individual rights, and constitutional governance, which would later shape his approach to political leadership in the Indian subcontinent.

Early Political Career:

Returning to India, Jinnah began his legal practice in Bombay (now Mumbai) and quickly gained recognition for his eloquence and legal acumen. Initially, he was associated with the Indian National Congress, the leading political party advocating for Indian independence. However, Jinnah's disillusionment with the Congress's approach, which he perceived as inadequate in safeguarding Muslim interests, led him to seek an alternative political platform.

Formation of the All-India Muslim League:

In 1913, Jinnah joined the All-India Muslim League, a political organization that aimed to protect the political rights of Muslims within the framework of a united India. Jinnah's entry into the League marked the beginning of a transformative phase in his political career. His leadership skills and commitment to the welfare of the Muslim community earned him the title of "Quaid-e-Azam" from his followers.

Champion of Muslim Rights:

Jinnah, through his speeches and writings, articulated the concerns and aspirations of the Muslim minority in British India. He firmly believed in the principle of separate electorates to ensure adequate representation for Muslims in legislative bodies. His advocacy for these political safeguards was rooted in the belief that Muslims, as a distinct religious and cultural community, needed protection from potential marginalization within a Hindu-majority political landscape.

Jinnah's efforts to secure political rights for Muslims culminated in the Lucknow Session of the All-India Muslim League in 1916, where the Congress and the League forged the Lucknow Pact. This agreement aimed to ensure adequate representation for Muslims in legislative bodies and marked a brief period of Hindu-Muslim unity in the larger struggle against British colonial rule.

Home Rule Movement and World War I:

During World War I, Jinnah actively supported the All-India Home Rule Movement initiated by Congress leaders Annie Besant and Bal Gangadhar Tilak. The movement sought self-governance for India within the British Empire. Jinnah's collaboration with Congress leaders during this period demonstrated his commitment to the broader cause of Indian self-rule.

However, as the war progressed, differences between the Congress and the Muslim League resurfaced, leading to a divergence in their political paths. The post-war period witnessed the emergence of Jinnah as the unequivocal leader of the Muslim League, steering it towards a more assertive pursuit of Muslim political rights.

Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms and the Khilafat Movement:

The Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms of 1919 introduced a system of dyarchy in the provinces and expanded the limited representation of Indians in legislative councils. While these reforms fell short of meeting the demands for self-governance, Jinnah's legal and constitutional expertise enabled him to navigate the intricacies of the new system.

Simultaneously, the Khilafat Movement, led by Muslim leaders seeking to protect the Ottoman Caliphate, gained prominence. Jinnah, recognizing the importance of Muslim unity, briefly cooperated with the Khilafat leaders, forming the short-lived "Congress-League Pact" in 1919. However, differences between the Congress and the League, especially regarding non-cooperation with the British government, led to the eventual collapse of this alliance.

Non-Cooperation Movement and Jinnah's Distancing:

The Non-Cooperation Movement, launched by Congress in 1920, aimed at boycotting British institutions. Jinnah, while sympathetic to the cause of Indian independence, was wary of the non-cooperation strategy. His skepticism about mass agitations and the potential for violence led to his growing alienation from the Congress leadership, including Mahatma Gandhi.

Jinnah's disagreements with Congress reached a turning point in 1928 with the clash over the Nehru Report. The report, drafted by Motilal Nehru and other Congress leaders, proposed a constitution for an independent India that failed to adequately address Muslim concerns. Jinnah, viewing it as a betrayal of the promises made to Muslims, distanced himself from the Congress and intensified his commitment to securing separate electorates and political safeguards for Muslims.

Demand for Separate Electorates:

Jinnah's demand for separate electorates for Muslims was rooted in his belief that, as a distinct religious and cultural group, Muslims required political representation commensurate with their numerical strength. This demand was an integral aspect of his vision for safeguarding minority rights within a united India.

The Simon Commission, appointed by the British government in 1927 to propose constitutional reforms, further intensified communal tensions. The Muslim League, under Jinnah's leadership, boycotted the Simon Commission, objecting to the absence of Indian representation.

Allahabad Address (1930) and the Two-Nation Theory:

In 1930, during the annual session of the All-India Muslim League in Allahabad, Jinnah delivered a historic address that laid the foundation for the Two-Nation Theory. He argued that Hindus and Muslims were distinct nations with their own religious, social, and cultural traditions, and their coexistence within a single state was not feasible. This theory formed the basis for Jinnah's subsequent demand for a separate Muslim state.

Jinnah's articulation of the Two-Nation Theory marked a significant ideological shift and underscored the growing realization that Hindu-Muslim unity, as envisioned during the early years of the Indian National Congress, was no longer tenable. The demand for a separate Muslim state gained momentum, especially in the context of continued Hindu-Muslim political differences.

Poona Pact and Communal Award:

In response to the demand for separate electorates, negotiations between Jinnah and leaders like Madan Mohan Malaviya resulted in the Poona Pact of 1932. The agreement ensured reserved seats for depressed classes (Scheduled Castes) within general electorates, addressing concerns about the political representation of the Dalit community.

Meanwhile, the Communal Award of 1932, announced by the British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, further accentuated the communal divide. The award provided separate electorates for various religious and social groups, solidifying Jinnah's insistence on separate representation for Muslims.

Jinnah's Vision for Pakistan:

As the demand for a separate Muslim state gained momentum, Jinnah continued to articulate his vision for Pakistan. He emphasized that the new nation would not only safeguard the political and economic rights of Muslims but would also uphold principles of justice, equality, and religious freedom. Jinnah envisioned a modern, democratic state where citizens, regardless of their religious affiliations, would enjoy equal rights and opportunities.

Contrary to some perceptions, Jinnah did not foresee Pakistan as a theocratic state. In his famous speech to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan on August 11, 1947, he reiterated the importance of religious freedom and equal citizenship, emphasizing that the state had no concern with the religion, caste, or creed of its citizens.

Role in the Quit India Movement (1942) and World War II:

During World War II, Jinnah initially supported the British war effort against fascism, seeing an opportunity for political concessions in return. However, the failure of the British government to meet the Muslim League's demands for significant constitutional changes led to Jinnah's withdrawal of support. The Quit India Movement of 1942, launched by Congress, aimed at forcing the British to leave India immediately. Jinnah, still disillusioned with the Congress and its leadership, kept the Muslim League aloof from the movement.

Post-War Scenario and Cabinet Mission Plan:

As World War II concluded, discussions on India's future intensified. The Cabinet Mission Plan of 1946 proposed a federal system for India with power-sharing arrangements between Hindus and Muslims. Jinnah reluctantly accepted the plan, hoping that it would pave the way for the creation of Pakistan as a separate state. However, the Congress's rejection of the plan and the subsequent outbreak of communal violence further fueled Jinnah's determination to achieve a separate homeland for Muslims.

1946 Elections and the Path to Partition:

The 1946 elections in British India were crucial in determining the future course of the subcontinent. The Muslim League performed exceptionally well in the provinces where it contested, especially in Punjab and Bengal. The success of the League in these elections solidified Jinnah's mandate to pursue the creation of Pakistan.

As communal tensions escalated, especially in Punjab, where violent clashes between Hindus and Muslims resulted in mass migrations and bloodshed, the demand for partition became more pronounced. Jinnah's unwavering commitment to the cause of Pakistan became evident during these tumultuous times.

Independence and the Birth of Pakistan:

The Mountbatten Plan of June 3, 1947, proposed the partition of British India into two independent dominions – India and Pakistan. Jinnah, despite his reservations about the truncated nature of Pakistan and the communal violence accompanying the partition, reluctantly accepted the plan. On August 14, 1947, Pakistan came into existence, and Jinnah assumed the office of Governor-General.

The partition, however, was marred by widespread violence and mass migrations, resulting in immense human suffering. Jinnah, deeply affected by the tragic events, emphasized the need for harmony and unity among the people of Pakistan.

Founding Father of Pakistan:

As Pakistan's first Governor-General, Jinnah faced the formidable task of building a new nation from scratch. He envisioned a democratic and pluralistic state where citizens enjoyed equal rights, irrespective of their religious background. In his address to the Constituent Assembly on August 11, 1947, Jinnah reiterated his commitment to the principles of justice, equality, and religious freedom.

Jinnah's leadership during the formative years of Pakistan laid the groundwork for a constitutional framework based on democratic principles. He emphasized the importance of a strong and impartial judiciary, a vibrant civil service, and respect for the rule of law. Despite his failing health, Jinnah continued to guide the nation in its early years.

Death and Legacy:

Unfortunately, Jinnah's health deteriorated rapidly, and he succumbed to tuberculosis on September 11, 1948, at the age of 71. His death was a significant loss for the young nation, as he left behind a legacy of vision, determination, and commitment to democratic values.

Jinnah's vision for Pakistan as a modern, democratic state faced challenges in the years following his death. The country grappled with political instability, military coups, and issues related to governance. However, Jinnah's principles continued to inspire successive generations of leaders and citizens.

Muhammad Ali Jinnah's life and legacy are indelibly woven into the history of the Indian subcontinent. His journey from a successful lawyer in British India to the founder of Pakistan reflects the complex political, social, and cultural landscape of the time. Jinnah's unwavering commitment to the rights of Muslims, his advocacy for a separate nation, and his vision for Pakistan as a democratic and inclusive state make him a pivotal figure in the struggle for independence.

While Jinnah's role in the creation of Pakistan is celebrated by many, his legacy remains a subject of debate and interpretation. Some view him as a statesman who navigated the challenging political terrain to secure a homeland for Muslims, while others critique aspects of his leadership and the subsequent trajectory of Pakistan's history.

Despite the challenges and controversies, Jinnah's ideals continue to resonate in Pakistan and beyond. The principles of justice, equality, and religious freedom that he championed remain integral to the aspirations of a democratic and pluralistic society. As Pakistan commemorates its founding father, the enduring impact of Jinnah's vision serves as a reminder of the ongoing quest for a just and inclusive nation.